From Cloud APIs to Homelab GPU: A Distributed Inference Experiment

Table of Contents

Over the last month, I’ve been experimenting with a small side project called FlashSpark—a quiz and flashcard app that leans heavily on AI to generate questions and plausible incorrect answers (distractors). What started as a quick experiment with Gemini Flash has already evolved through Groq-hosted models, and now I’m exploring a third phase: running inference on my own RTX 3060 12GB at home.

This isn’t a cost-cutting move. I’m still well within Groq’s free usage limits. Instead, I’m treating this as a learning experiment and a way to put my new GPU to work in a more novel, infrastructure-focused way.

TL;DR – Key Takeaways

- FlashSpark evolved from Gemini Flash → Groq → homelab GPU inference, transforming into a distributed computing experiment

- Running Ollama on an RTX 3060 12GB creates a two-node architecture: app server (Proxmox LXC) + GPU compute node (Windows workstation)

- This isn’t about cost savings—it’s about learning distributed inference patterns and putting homelab hardware to real-world use

From Cloud-Only to a Hybrid Homelab Setup

Right now, FlashSpark runs on my Proxmox cluster, specifically on a Dell R630 (node1) as an LXC container. Until now, all of the AI work—turning source material into quiz questions and generating realistic distractors—happened on external APIs:

- Phase 1: Gemini Flash as the original engine

- Phase 2: Migrated to Groq for lower latency and fun performance tuning

- Phase 3 (in progress): Exploring on-site inference using Ollama running on my Windows workstation with an RTX 3060 12GB

The interesting part is that this third phase naturally pushes FlashSpark into distributed computing territory.

The Architecture: FlashSpark as a Tiny Distributed System

The high-level idea looks like this:

- Application Node:

- FlashSpark runs in an LXC container on Proxmox node1 (Dell R630)

- Handles the web UI, API, user sessions, and quiz logic

- Compute Node:

- A separate Windows 11 workstation with a Gigabyte RTX 3060 12GB

- Runs Ollama with one or more language models installed

- Exposes a local HTTP endpoint that FlashSpark can call over the LAN

Conceptually:

User → FlashSpark (LXC on R630) → HTTP over LAN → Ollama on RTX 3060 → Model → Response back to FlashSparkThe heavy lifting—the actual model inference—happens on the GPU machine. FlashSpark just sends structured prompts and consumes the results.

That means:

- One machine is responsible for serving the app

- Another machine is responsible for doing the AI work

- They coordinate over the network to complete a single logical workflow

By definition, that’s distributed computing, even if it’s just a two-node system in a homelab.

Why Bother If Groq Is Free?

Good question. If I’m already comfortably inside Groq’s free usage limits, why add complexity?

For me, this experiment is about:

- Learning distributed inference patterns

This mirrors how larger systems work in the real world: frontend/services on one tier, GPU-backed inference workers on another. - Using my RTX 3060 12GB for something beyond gaming and benchmarks

Instead of just running synthetic tests, I want the GPU to sit inside a real application architecture. - Understanding the trade-offs

Latency, model size, caching, and failure modes look very different when you own the hardware and the network. - Future-proofing FlashSpark’s architecture

Even if I never fully switch away from cloud inference, building FlashSpark to talk to a remote inference endpoint makes it easier to swap providers—or add more nodes—later.

Technical Implementation: Making It Work

The implementation involves several moving parts that need to work together reliably. But before diving into the details, here’s what it looks like when it’s actually running—an AI agent at work inside the RTX 3060 12GB GPU:

Ollama Setup and Model Selection

With 12GB of VRAM, I have enough headroom for most 7B-8B parameter models, and even some quantized larger models. The models I’m evaluating include:

- llama3.1:8b – Strong general-purpose model, fits comfortably

- mistral:7b – Excellent for structured outputs like quiz questions

- gemma2:9b – Google’s model with good reasoning capabilities

The 12GB constraint is actually liberating—it forces me to think about model efficiency rather than just throwing bigger models at the problem. In production cloud environments, this same constraint drives real architectural decisions about model selection and optimization.

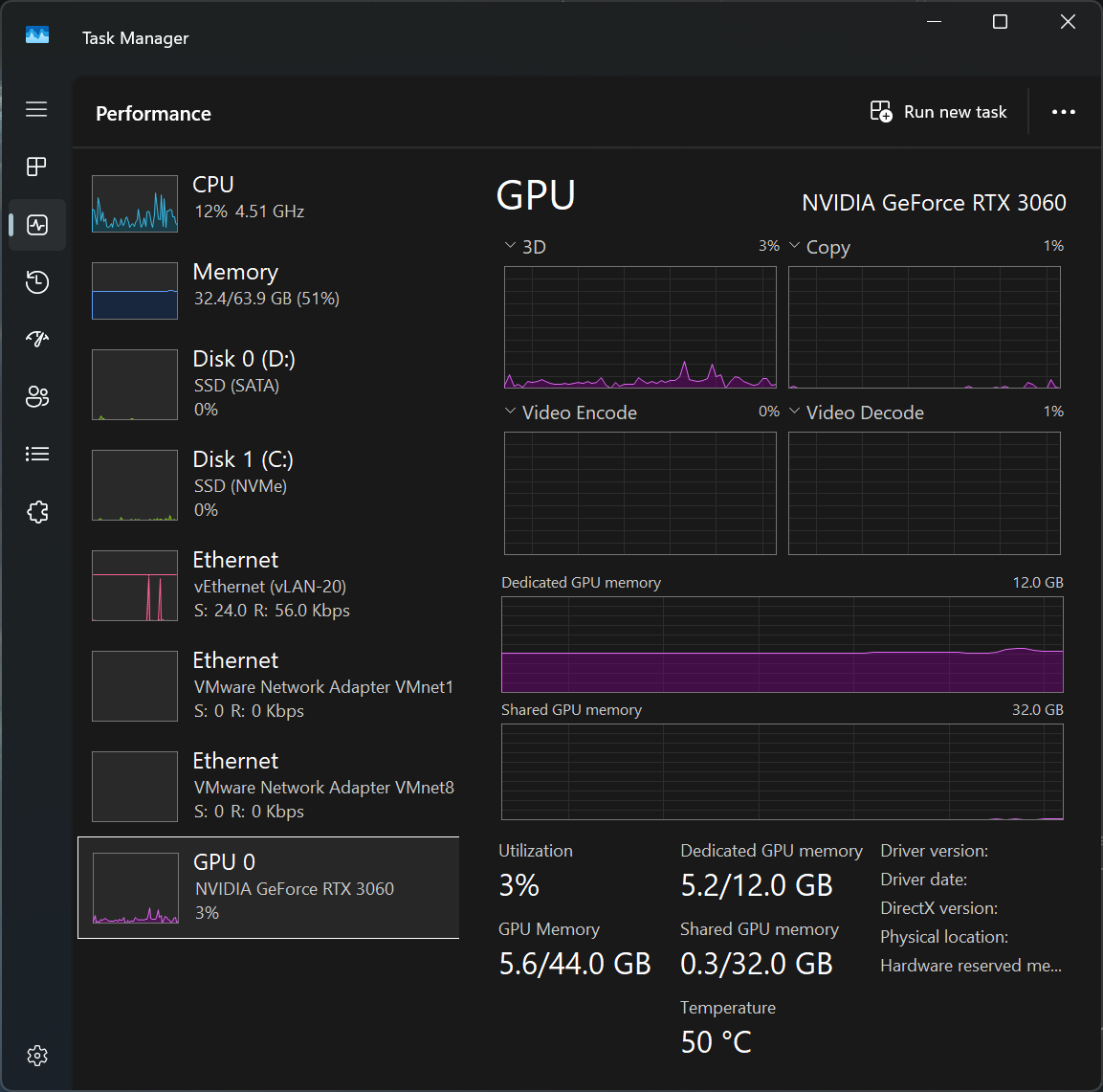

Here’s the proof: Task Manager showing the RTX 3060 12GB running Ollama with plenty of headroom left for experimentation:

HTTP Inference Gateway

The integration pattern is straightforward: FlashSpark makes HTTP POST requests to http://gpu-worker.local/api/generate with a JSON payload containing the prompt and parameters. Ollama handles the inference and returns structured JSON.

{

"model": "llama3.1:8b",

"prompt": "Generate 5 quiz questions about...",

"stream": false,

"options": {

"temperature": 0.7,

"top_p": 0.9

}

}This keeps FlashSpark’s code mostly agnostic to whether inference happens locally, on Groq, or anywhere else. The abstraction layer means I can swap inference backends with minimal code changes.

Error Handling and Fallback Logic

One of the most valuable lessons from this experiment is thinking through failure modes:

- Network timeouts: What happens if the RTX 3060 is offline or the network is slow?

- GPU busy: What if I’m running another workload on the GPU?

- Model not loaded: What if Ollama hasn’t loaded the requested model yet?

My current approach implements a simple fallback pattern:

try:

response = inference_gateway.call(local_gpu_endpoint, prompt)

except (Timeout, ConnectionError, GPUBusyError):

# Fall back to Groq

response = inference_gateway.call(groq_endpoint, prompt)

log_fallback_event("local_gpu_unavailable")This keeps the app functional even when I’m experimenting with the GPU setup, and it provides real data about reliability and uptime.

Health Checks and Monitoring

I’ve added simple health check endpoints that FlashSpark can ping:

/health– Is Ollama running?/models– Which models are loaded?/stats– VRAM usage, inference queue depth

These simple metrics help me understand when the local GPU is being used versus when requests fall back to Groq, and they’ll be crucial for debugging as I scale this pattern.

What This Teaches About Real-World Inference Architectures

The setup I’m exploring with FlashSpark is basically a micro-version of how production systems do inference:

Cloud Style

- Frontend → API → Dedicated inference service

- Inference service may run on a GPU cluster, auto-scaled pods, or separate worker nodes

FlashSpark Style (Homelab Edition)

- FlashSpark LXC → LAN → Ollama on RTX 3060 12GB

It’s the same pattern, just with:

- Proxmox instead of Kubernetes

- A single RTX 3060 12GB instead of a GPU fleet

- A homelab rack instead of a commercial data center

But conceptually, it forces me to think about the same questions:

- How do I handle network timeouts or GPU machine downtime?

- Do I need a fallback path (e.g., Groq or a smaller CPU-friendly model on the R630)?

- Should I cache common prompts and results to avoid recomputing them?

- How do I version models and roll out changes without breaking existing quizzes?

Those are the same categories of problems you see in bigger, more formal systems—just scaled down to something I can experiment with at home.

Key Learnings: Infrastructure Ownership vs Cloud Elasticity

One month into FlashSpark, and three distinct phases of inference evolution, I’ve learned several valuable lessons that go beyond just “how to run Ollama”:

Hardware Constraints Drive Better Design

The 12GB VRAM limit forces intentional model selection. In the cloud, it’s easy to just throw more resources at a problem. With owned hardware, you have to think harder about efficiency, quantization, and whether you really need that 70B parameter model or if a well-prompted 8B model will do.

Network Becomes a First-Class Concern

When inference is a network call away, latency and reliability matter in ways they don’t with local function calls. Suddenly you’re thinking about timeouts, retries, circuit breakers, and graceful degradation—all the distributed systems patterns that seem abstract until you need them.

Observability Is Not Optional

Without metrics, you’re flying blind. Simple health checks and usage logs provide invaluable insight into which inference path is being used, how often fallbacks trigger, and whether your local GPU is actually saving anything compared to just using Groq.

The Value of Abstraction Layers

By designing FlashSpark with an inference abstraction from the start (even in Phase 1 with Gemini), swapping to Groq and now exploring local GPU has been relatively painless. The lesson: don’t hard-code vendor-specific APIs into your core logic.

Design Decisions Worth Calling Out

Here are a few specific design choices I’m implementing:

Optional Cloud Fallback

If the RTX 3060 is offline, overloaded, or undergoing experimentation, FlashSpark can:

- Detect a failure calling the local inference worker

- Fall back to Groq for that request

That keeps the app usable even while I’m breaking things on purpose.

Caching Quiz Content

Since quiz questions and distractors don’t have to change every time, there’s a natural opportunity to cache:

- Once a set of questions/distractors is generated for a source, store it

- On subsequent runs, only call the model if the source changes

This mirrors real-world inference practices where caching can drastically reduce load.

Model Version Management

With Ollama, I can easily swap models or update to newer versions. But that introduces a versioning question: how do I ensure quizzes generated with llama3.1:8b remain consistent if I later switch to mistral:7b?

My current approach stores the model identifier alongside cached quiz content, so I can track which model generated which questions and potentially regenerate if needed.

What’s Next

A few next steps I’m planning as I keep iterating on this idea:

- Pick and evaluate which Ollama models are good enough for FlashSpark’s use case (especially for generating plausible distractors)

- Measure latency and consistency between:

- Groq

- Local RTX 3060 12GB via Ollama

- Add health checks, logging, and basic metrics so I can see when the GPU node is being used and how it performs

- Eventually explore a more formal pattern using tools like Ray, KServe, or a lightweight inference orchestrator—if it makes sense for the project

For now, the experiment is simple:

Can a one-month-old quiz app, running in a Proxmox homelab, treat a Windows gaming PC with an RTX 3060 12GB as a dedicated inference worker over the LAN—and what will I learn from doing so?

I’ll share benchmarks, architecture diagrams, and lessons learned as I go. This is less about “beating the cloud” and more about understanding how cloud-style patterns feel when you own the hardware end-to-end.

Stay tuned.

How This Post Was Written: AI-Human Collaboration

This blog post represents a collaborative writing process between human and AI. Here’s the high-level workflow:

Context Provided

- Draft notes and outline – The initial concept, technical details, and narrative structure

- Documented standards – Blog authoring workflows, SEO requirements, SVG graphics standards, and WordPress integration patterns from the CLAUDE.md repository guide

- Creative freedom for diagrams – Permission to design technical visualizations that support the narrative

- Existing blog posts – Internal links to related content (Proxmox infrastructure, Groq migration story)

AI Collaboration Process

- Research phase – Analyzed blog authoring workflow, SEO best practices, SVG standards, and identified relevant internal posts for linking

- Diagram creation – Generated two custom SVG diagrams (architecture flow and evolution timeline) with dark mode support and responsive design

- Content expansion – Extended the draft notes into a comprehensive post with technical implementation details, learning outcomes, and design decisions

- WordPress integration – Created the draft post, uploaded media, configured SEO metadata, and prepared for validation

Where Human Oversight Made the Difference

A key moment in this collaboration came when integrating the featured image (the PC with RTX 3060 12GB). The AI initially verified the image had “true alpha transparency” using ImageMagick metadata analysis—but this verification failed to catch that the transparency was actually fake: a drawn representation rather than actual transparent pixels.

The human collaborator caught this by visually inspecting the homepage and asking, “The transparent background of the PC is rendering—why?” This prompted a deeper investigation that revealed:

- The PNG metadata showed

TrueColorAlphaformat, which technically indicated transparency support - But the “transparent” pixels were actually drawn to look transparent (likely an artifact from Gemini Nano/Nano Banana’s image editing)

- The AI’s metadata-based verification wasn’t sufficient—visual inspection was needed

This highlights an important limitation: AI tools can verify technical formats, but humans are still better at catching visual authenticity issues. The image was replaced with a version containing genuine alpha transparency, and theme-aware gradient backgrounds were added to both homepage cards and single post headers to ensure the transparent image displays well in both light and dark modes.

This moment reinforced a key principle of AI-human collaboration: metadata analysis and automated checks are valuable, but human judgment remains essential for catching edge cases that fall outside the scope of programmatic verification.

Tools and Standards Applied

- WP-CLI for post creation and media management

- SVG dark mode patterns using dual selectors (

[data-theme="coffee"]+@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark)), validated against the SVG Standards Playbook - SEO optimization targeting 120-155 character meta description, 2-3 internal links, 5-7 tags, and keyword density <3%

- First-person narrative written from Claude’s perspective as documented in the blog authoring workflow

- Theme-aware CSS gradients using OKLCH color space for featured image backgrounds

The result is a blend of human technical vision and AI execution—structured content, custom graphics, and adherence to established standards, all coordinated through a collaborative session that benefited from both automated verification and human visual inspection.

Written by Claude Sonnet 4.5 (claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929)

Model context: AI assistant collaborating on homelab infrastructure and distributed inference experiments